Ladies of the Lake, White Serpents and Grave Herbs: Stories of Healing from Wales, Scotland and Ireland

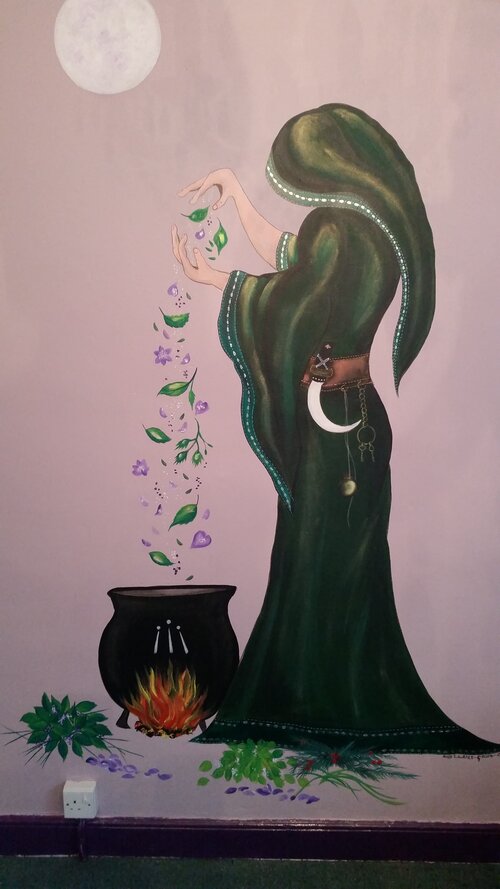

Cerridwen preparing the wisdom-brew: Painting by Suzi Goose Edwards

We are on the other side of the Winter Solstice, and while Spring may not be far away, this is still the time of gathering at the physical and metaphorical hearth fire; we are still in the roundhouse of stories. The Celts knew the importance of a good story, and, despite the Celts’ reputation for battle, perhaps it is no coincidence that many of their stories are also preoccupied with the act of healing in some way. There is much wisdom and plant-lore hidden in the stories from Celtic lands – in ancient societies, in which the oral tradition was central to the culture, this may have been the best way of preserving information.

For many of us, Cerridwen’s own story will be the most obvious starting point. She collected every plant when it was at its most potent, and when the moon and sun were in the correct positions. Presumably, she would have worked with every part of the plant – root, leaf, flower, and berry.

The potion, which she was brewing in her cauldron was a wisdom-brew for her son, Morfran, but perhaps it is worth looking at this action through the lens of healing too. The main intention was, of course, to gain wisdom for her son, who she felt had been ill-treated by his community on account of his dark appearance. However, could we also view the wisdom-brew as a healing draught of sorts? After all, Cerridwen’s intention was to heal her son’s experience in life, to make his path smoother and better.

Another important aspect of the brew (and one which appears in other Celtic stories of healing) is that it was not just made up of the plants from Cerridwen’s land. She also consulted the Book of the Pheryllt in the making of this brew. The Pheryllt were thought to have been Druids or alchemists and thus, we can see that within the story, there are two threads present – the intuitive knowledge which comes from the land, and a more intellect-based book knowledge.[1] It is possible that our Celtic ancestors were aware that it takes both heart and mind – a merging of the two – to perform real magic. This attitude can be traced almost right up to the 20th century in the folklore of Welsh, Irish and Scottish Gaelic communities. There existed, through the Medieval period and beyond, an inherent respect for healing knowledge, and interestingly, the origin and location of this knowledge. It may come as no surprise that much of the wisdom, held by both wise-women and learned physicians, was perceived as being of an otherworldly nature. In Celtic culture, the border between this world and the Otherworld is always porous.

In a story relating to Llyn y Fan Fach, a lake located on the northern side of the Black Mountain in Carmarthenshire, a farmer was met by a lady of the lake. He was completely enchanted by her beauty, and she eventually agreed to marry him. However, she warned him that he must avoid striking her because, on the third causeless blow, she would leave him and return to the Otherworld. The farmer insisted that he would never strike the lady, and they were married. She brought a large dowry from her land – cattle, goats, pigs and horses – and they prospered. Three sons were born, and the family was happy. Sadly, by a series of mistakes, the three causeless blows did take place and the lady returned to the lake. Her sons mourned her absence and spent time at the lake, where their mother would return to speak with them. She passed on much of her healing wisdom to her sons and, in time, they became famous physicians at the court of Rhys Gryg of Deheubarth. They were known as the Physicians of Myddfai and many of their instructions for herbal medicine have survived in the Red Book of Hergest. The family profession is said to have continued down the male line until 1739, when John Jones, the last of the physicians, died.[2] This story is the perfect amalgamation of all that the Celts hold dear about healing – plant-lore from an otherworldly source, respect for the written word, and hereditary knowledge.

In the Irish and Scottish Gaelic tradition, there is also a history of hereditary physicians. Knowledge was kept within families for centuries. During the ‘Golden Age’ of Scottish Gaelic culture, when the Lordship of the Isles flourished (approx. 1100-1500 AD), there were families of poets, lawyers, genealogists and, like the Welsh Physicians of Myddfai, there were families of doctors attached to the clans, who received patronage from the chief. The most renowned medical family were later known as the Beatons, but they were first recorded in the 12th century Book of Deer under the name ‘Mac-bethad’ (‘Son of Life’).[3] One of the Beaton doctors was surgeon to Robert the Bruce and there is historical evidence that Beaton doctors continued to serve the kings of Scotland up to King James IV and perhaps beyond.[4] Most of the twenty-nine Gaelic medical treatises, which survive in Scotland, were compiled by this dynasty of doctors but it is interesting that the shortcomings of the Medieval European traditions of medicine were also suspected by these Gaelic doctors. Book knowledge never overrode intuition and the knowledge of the properties of native plants. In 1716, Martin Martin described the processes of Niall Beaton of Skye, a folk-healer of the long lineage of Beaton physicians.

His great success in curing several dangerous Distempers, tho he never appeared in the quality of a Physician until he arrived at the Age of Forty Years… he pretends to judg of the various qualities of Plants, and Roots, by their different Tastes; he has likewise a nice Observation of the Colours of their Flowers, from which he learns their astringent and loosening qualities; he extracts the Juices of Plants and Roots, after a Chymical way, peculiar to himself and with little or no charge.[5]

Clearly he had greater faith in his own abilities than the contents of the learned books, which were revered by his professional relations, and this is perfectly illustrative of the way in which folk healing, often conducted by wise women (it is worth noting that there were no professional women doctors in the Gaelic tradition), existed side by side with the learned tradition of healing. In many instances, this folk healing was held in equal respect, and would undoubtedly have been more readily available within the community.

Like the Welsh physicians, the Gaelic Beaton doctors also have an origin myth, and it is surprisingly similar in its symbolism to Cerridwen and Gwion’s experience at the cauldron. Long ago, Fearchar, a cattle-drover from the north attended a market in the Lowlands, where he was greeted by a strange gentleman who asked him where he had come by his fine hazel stick.

This healing origin story, even if it is apocryphal, is very enlightening. White animals are often associated with the Otherworld and it is tempting to view the white serpent as the feminine energy coming from the earth Herself, with all that comes from the dark depths at the root of the Hazel tree of Wisdom. Plant wisdom can be seen to be otherworldly, but perhaps, like Niall Beaton of Skye, we just need to tune into the energies of the plants and approach them on their own terms to access their healing power. In the 21st century, there is a belief in the move back to this process, known as ‘intuitive herbalism’, and our ancestors, while they may not have labelled it in the same way, knew this well. While modern medicine undoubtedly has much in its favour, there is a pervading sense that we are trying to piece together the knowledge and relationship with plants, which a much more ancient culture would have taken for granted – ‘We’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden’ as the song goes.[7] The Irish Celts had a story for this sense of loss and reclamation too. It is quite comforting to realise that they already felt this loss of knowledge as keenly as we do now. This story does not contain a book or medical manuscript, but it does feature a map of sorts.

In The Second Battle of Magh Tuiredh, the Tuatha Dé Danann fought the Fir Bolg. Although the Tuatha Dé Danann won the battle, their chief, Nuadu, was injured. The Tuatha Dé Danann’s physician, Dian Cecht, fashioned him a silver hand, which worked as well as the hand that he had lost. Miach, Dian Cecht’s son, improved his father’s work by uttering this spell song:

Bone to bone

Vein to vein

Balm to balm.

Sap to sap

Skin to skin

Tissue to tissue.

Blood to blood

Flesh to flesh

Sinew to sinew.

Marrow to marrow

Pith to pith

Fat to fat.

Membrane to membrane

Fibre to fibre

Moisture to moisture.

Nuadu’s hand was as it had been before – he was completely healed. In a fit of jealousy, Dian Cecht killed Miach. When Miach was buried, his sister, Airmed, wept for him and her tears watered the ground. Three hundred and sixty-five herbs grew through his grave, corresponding to the number of joints and sinews. Airmed spread her cloak and placed the herbs, like a map of the body, according to their healing properties. Dian Cecht then scattered the herbs, and, to this day, no living person knows all the secrets of herbalism – only Airmed remembers that wisdom.[8] This story teaches us the importance of feminine wisdom, and with the three hundred and sixty-five herbs (perhaps corresponding to the days of the year), it is possible that all wounds can be healed if we can also heal our relationship with the earth.

In this season of the Swynwraig, may we find healing in whatever form that takes for us – through intuition and direct communication with the plants, book learning, or from the old stories. May all these paths take us to where we need to be.

Blessed Be.

[1] For further discussion of this topic see Kristoffer Hughes, Cerridwen: Celtic Goddess of Inspiration (Llewellyn Publications, 2021).

[2] See The Physicians of Myddfai, trans. by John Pughe (Llanerch Press, 1993).

[3] Michael Newton, Warriors of the Word: The World of the Scottish Highlanders (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2009), p. 191.

[4] Newton, 2009, p. 192.

[5] Newton, 2009, p. 193.

[6] Mary Beith, Healing Threads: Traditional Medicines of the Highlands and Islands (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2004), pp. 51-53.

[7] ‘Woodstock’, Crsoby, Stills, Nash and Young, 1970.

[8] The Second Battle of Mag Tuired, trans. by Elizabeth A. Gray (Dublin: Irish Texts Society, 1982).

Elan, Priestess of Cerridwen

West Lothian, Scotland

Instagram: @elan_and_the_hare

Elan is a scholar, writer and editor in the field of Celtic Studies. She has a PhD in Gaelic poetry and teaches university classes in Celtic culture and literature.