‘Mother’s arms with love caressing’: Lullabies in the Celtic Tradition

When we think of Cerridwen singing, the first image which may come into our minds is of the spell song singer, standing over Her cauldron, adding plants to Her brew and singing magical incantations. This is of central importance in Cerridwen’s story. The wisdom brew, which took a year and a day to come to fruition, was sung into existence – Cerridwen’s breath in the form of air, meeting earth, fire and water. We can trace the effort put into this task to Cerridwen as Mother. The brew was for Her son. This leads us to this season’s aspect of our Goddess – Cerridwen the Great Mother, the protector and nurturer of Her kin. I have been dreaming into the other sorts of songs we might attribute to Cerridwen, in Her aspect as Mother. As a mother, She undoubtedly would have sung lullabies to Her children and perhaps lullabies (those songs which magically settle and calm a child and rock them to sleep) are spell songs of a fashion!

The songs shared between mother and child often come naturally to us. Lullabies are some of the oldest and simplest of songs, because the urge to protect and calm a child is ancient and primal. I remember the lullabies my mum sang to me (probably because they were still in her repertoire when I was old enough to put myself to sleep!). These songs stick in our minds because we sing them constantly and, if we are blessed with a song lineage of sorts, we can perhaps pass them on to our own children. When I was pregnant with my daughter, I imagined all the fancy songs I would sing to her and yet, in those days after she was born, the minute she was restless and would not sleep, I reverted back to the old favourite of my mum and my gran, the Scottish lullaby, ‘Ally Bally Bee’. It was unavoidable – ‘Ally Bally Bee’ is deep in my bones. This Scots song is well-known but I wasn’t content to just sing the first few verses I had known as a child. Motherhood couldn’t quite quash the researcher in me, and I taught myself the other lesser-known verses too.

Ally bally, ally bally bee,

Sittin’ on yer mammy’s knee,

Greetin’ for a wee bawbee,

Tae buy some Coulter’s candy.

Poor wee Jeanie’s getting’ awfy thin,

A rickle o’ banes covered ower wi’ skin,

Noo she’s getting’ a wee double chin,

Wi’ sookin’ Coulter’s Candy.

Mammy gie’s ma thrifty doon,

Here’s auld Coulter comin’ roon’,

Wi’ a basket on his croon,

Selling Coulter’s Candy.

When you grow old, a man to be,

You’ll work hard and you’ll sail the seas,

An’ bring hame pennies for your faither and me,

Tae buy mair Coulter’s Candy.

Coulter he’s a affa funny man,

He maks his candy in a pan,

Awa an greet to yer ma,

Tae buy some Coulter’s candy.

Little Annie’s greetin’ tae,

Sae whit can puir wee Mammy dae,

But gie them a penny atween them twae,

Tae buy mair Coulter’s Candy.(1)

The lullaby is not particularly old (but it is old enough to feel part of my own family’s history). It was written by a former Galashiels weaver, Robert Coltart (1832–1880) and was an advertising jingle for the aniseed-flavoured sweets that he manufactured in Melrose in the Scottish Borders and sold around the Borders markets and fairs.(2) In 1958, a letter to The Weekly Scotsman reported that a man remembered hearing it from his grandmother, who in turn had learned the song around 1845.(3) What I find fascinating is that while the recipe for the ‘Coulter’s Candy’ is no longer known, the song is remembered by many. Thus, the ‘taste’ is in the song itself. I recently sang the lullaby again to my daughter, who turned 5 last month. The song had not been on my lips for a number of years and yet the look of recognition on her face was clear – she remembered it at some deep level. The songs we sing to our babies as we nurture them in their earliest months are not forgotten.

I will always remember the time I was sitting on a South Devon promenade, nursing my daughter. It was our first holiday a few months after she was born and I was singing a ‘silly song’ to her under my breath – the type of song where you rhyme her name with other things. It certainly would not have won an award for lyrics! And yet a grandmother sitting close by struck up a conversation with me. She sang me a ‘silly song’ of her own, which she had sung to her daughter and then, more recently to her granddaughter. We both cried a few tears by the sea that day – me, with the hormones of early motherhood raging through my system, and that beautiful grandmother, who had had a lifetime of wisdom of ‘made-up songs’, ditties and lullabies, remembering her experiences of motherhood.

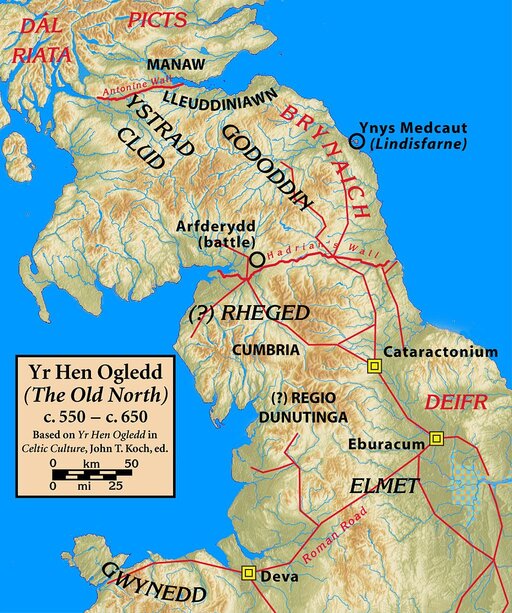

There are many examples of lullabies in the Celtic countries. The oldest lullaby ‘Dinogad’s Smock’ or ‘Dinogad’s Cloak’ is a lullaby in Old Welsh. The mother recounts the hunting prowess of the dead father of an infant named Dinogad, who is wrapped in a smock made of marten skins. It is both a lullaby and a lament for her husband and it was contained in the 13th-century Book of Aneirin. While we think of Welsh as being restricted to the geographic location of modern Wales, Old Welsh was also spoken further north in what was known as Yr Hen Ogledd (4), and it is thought that this lullaby came from an older text which originated during the second half of the 7th century in the Kingdom of Strathclyde, Scotland.

Image courtesy of https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0 via Wikimedia Common

The lullaby describes the smock and then lists the animals which were caught in the past by Dinogad’s father.

Peis dinogat e vreith vreith.

o grwyn balaot ban wreith.

chwit chwit chwidogeith.

gochanwn gochenyn wythgeith.

pan elei dy dat ty e helya;

llath ar y ysgwyd llory eny law.

ef gelwi gwn gogyhwc.

giff gaff. dhaly dhaly dhwg dhwg.

ef lledi bysc yng corwc.

mal ban llad. llew llywywg.

pan elei dy dat ty e vynyd.

dydygai ef penn ywrch penn gwythwch pen hyd.

penn grugyar vreith o venyd.

penn pysc o rayadyr derwennyd.

or sawl yt gyrhaedei dy dat ty ae gicwein

o wythwch a llewyn a llwyuein.

nyt anghei oll ny uei oradein.

Dinogad’s smock, speckled, speckled,

I made it from the skins of martens.

Whistle, whistle, whistly

we sing, the eight slaves sing.

When your father used to go to hunt,

with his shaft on his shoulder and his club in his hand,

he would call his speedy dogs,

‘Giff, Gaff, catch, catch, fetch, fetch!’,

he would kill a fish in a coracle,

as a lion kills an animal.

When your father used to go to the mountain,

he would bring back a roebuck, a wild pig, a stag,

a speckled grouse from the mountain,

a fish from the waterfall of Derwennydd

Whatever your father would hit with his spear,

whether wild pig or lynx or fox,

nothing that was without wings would escape.(5)

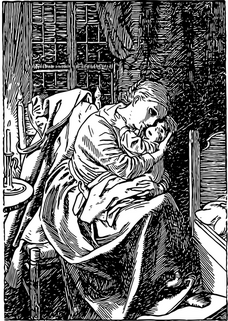

Another Welsh lullaby, considerably more recent in date, which I first heard sung so beautifully by one of my sisters, Priestess Gail Spiritstar, is ‘Suo Gân’ (‘lull song’). It first appeared in print around 1800 and the lyrics were also recorded by the Welsh folklorist Robert Bryan (1858–1920)(6). I can easily imagine that the words and sentiment behind the lullaby – that sense of love and protection – is something which would have been shared by Cerridwen for Her own children.

Huna blentyn ar fy mynwes,

Clyd a chynnes ydyw hon;

Breichiau mam sy’n dynn amdanat,

Cariad mam sy dan fy mron;

Ni chaiff dim amharu’th gyntun,

Ni wna undyn â thi gam;

Huna’n dawel, annwyl blentyn,

Huna’n fwyn ar fron dy fam.

Huna’n dawel, heno, huna,

Huna’n fwyn, y tlws ei lun;

Pam yr wyt yn awr yn gwenu,

Gwenu’n dirion yn dy hun?

Ai angylion fry sy’n gwenu,

Arnat ti yn gwenu’n llon,

Tithau’n gwenu’n ôl dan huno,

Huno’n dawel ar fy mron?

Paid ag ofni, dim ond deilen

Gura, gura ar y ddôr;

Paid ag ofni, ton fach unig

Sua, sua ar lan y môr;

Huna blentyn, nid oes yma

Ddim i roddi iti fraw;

Gwena’n dawel yn fy mynwes.

Ar yr engyl gwynion draw.

To my lullaby surrender,

Warm and tender is my breast;

Mother’s arms with love caressing

Lay their blessing on your rest;

Nothing shall tonight alarm you,

None shall harm you, have no fear;

Lie contented, calmly slumber

On your mother’s breast my dear.

Here tonight I tightly hold you

And enfold you while you sleep,

Why, I wonder, are you smiling

Smiling in your slumber deep?

Are the angels on you smiling

And beguiling you with charm,

While you also smile, my blossom,

In my bosom soft and warm?

Have no fear now, leaves are knocking,

Gently knocking at our door;

Have no fear now, waves are beating,

Gently beating on the shore.

Sleep, my darling, none shall harm you

Nor alarm you, never

And beguiling those on high.(7)

Image by Jo Justino of Pixabay

Lullabies perhaps tell us more about the experience of the singer, than they do about the child in their arms. In the Celtic tradition, these lullabies can provide hints of social, political, and economic anxieties because, after all, the fears for the future are never more obvious than when the future is lying in your arms in the form of a child. The Scottish Gaelic lullaby, ‘Bà bà mo leanabh beag’, dates from the time of the potato famine in the mid-1880s and is a poignant example from the song record of a time when, despite the Highlander’s own food source, the potato, becoming depleted, exports of grain continued. In the spring of 1847, the sight of grain leaving the ports of the eastern Highlands incited protests and in the Caithness port of Wick rioters raided the grain stores.(8) The words in the lullaby show the effects of starvation at the most personal level. The simplest and most immediate of words are often best at conveying the Gaelic lyrical cry.

Bà bà mo leanabh beag

(Ba ba my wee baby)

Bidh thu mòr, ged tha thu beag

(You will be big, though you are small)

Bà bà mo leanabh beag

(Ba ba my wee baby)

Chan urrainn mi gad thàladh

(I cannot lull you)

Dè a ghaoil a nì mi ruit?

(What, my dear, will I do with you?)

Dè a ghaoil a nì mi ruit?

Dè a ghaoil a nì mi ruit?

Gun bhainne cìche agam dhut

(Without breastmilk to give you?)

Gun bhainne cìche agam dhut

(without breastmilk to give you)

Gun bhainne cìche agam dhut

Gun bhainne cìche agam dhut

Eagal orm gun gabh thu cruip

(I am afraid you might get croup)

Eagal orm gun gabh thu cruip

(I am afraid you might get croup)

Eagal orm gun gabh thu cruip

Eagal orm gun gabh thu cruip

Le buigead a’ bhuntàta

(With the softness of the potatoes)(9)

In my research of the Celtic song tradition, I have noticed that many lullabies are not necessarily happy songs. It is clear that a lullaby was also a method for the mother of allowing her thoughts, experiences and feelings to flow (perhaps to match the flow of her breastmilk?). These lullabies are cathartic expressions of motherhood. I wonder what words came to Cerridwen as She rocked Her son, Morfran? What concerns for his future escaped through Her song as she gazed down at him? And did She sing to Taliesin before She placed him in the leather bag, readying him for his journey into another world? These lullabies are lost to time, but perhaps, in the future, we can give voice to Her experience of motherhood with new lullabies yet to be composed by Her kindred.

Blessed Be.

References

1. James T. R. Ritchie, The Singing Street (Oliver & Boyd, 1964).

2. https://web.archive.org/web/20131019070839/http://www.bordertelegraph.com/articles/1/23740 (accessed 29/6/23)

3. Norman Buchan, 101 Scottish Songs (Collins, 1962).

4. Koch, John T., Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, (ABC-CLIO, 2006), p516

5. Kenneth Jackson, The Gododdin: Scotland’s oldest Poem (Edinburgh University Press, 1969).

6. Barbara and Michael Cass-Beggs, Folk Lullabies of the World. (Oak Publications, 1993).

7.Barbara and Michael Cass-Beggs, Folk Lullabies of the World (Oak Publications, 1993).

8. http://www.kistodreams.org/index.asp?pageid=651584 (accessed 29/6/23)

9. http://www.kistodreams.org/index.asp?pageid=651584 (accessed 29/6/23)

Elan, Priestess of Cerridwen

West Lothian, Scotland

![In this season of Water on Cerridwen’s Wheel of the Year, we have reached the point when summer is properly upon us; many people are turning to the thought of holidays and others are gearing up for music festivals across the country. This is the time when ‘going with the flow’ seems like a good plan! Hard work can wait for a while – perhaps ‘messing about on boats’ on the river as the Water Rat said to the Mole really is the answer. As I explore the folk song tradition through the lens of Cerridwen of Water, I am thinking of a concept, which has its source in the symbolism of water and which never fails to inspire and move me – that of the Carrying Stream. The Carrying Stream comes from a poem, composed by the Scottish folk collector, ethnologist and poet, Hamish Henderson. Should there be a name and credit here? These are words from an elegy, which he wrote for himself: Change elegy into hymn, remake it – Don’t fail again. Like the potent Sap in these branches, once bare, and now brimming With routh of green leavery, Remake it, and renew. Maker, ye maun sing them … Tomorrow, songs Will flow free again, and new voices Be borne on the carrying stream. This Carrying Stream has come to mean being part of the passing on of a tradition, mainly through music and culture. Henderson, who was one of the first folk collectors in the School of Scottish Studies in Edinburgh (a treasure house of tradition and the ‘voice of the people’ established in 1952 in George Square, at the University of Edinburgh). He knew the value of song and tradition and he travelled all over Scotland, collecting songs and stories from the people he met. He is well-known for the relationships he formed with the Traveller communities – those who were ‘Summer Walkers’ and the berry pickers of Blairgowrie. It is significant that it was often the Travelling community who were the best source of knowledge for the ‘old songs’. These people were often shunned and derided and yet it was their characteristic movement across the land (the reason for many peoples’ distrust of them) that enabled them to pick up songs from many places and carry them forward. Henderson’s ‘discovery’ of the ballad singer, Jeannie Robertson was described by Henderson as ‘the most important, single achievement of my life – the thing of which I am most proud.’ Should there me a name and credit here? She was a Traveller with a vast storehouse of traditional knowledge and song. In 1941, in Poetry and Prophecy, the archaeologist N.K. Chadwick had written that ‘among the early Celtic peoples the inculcations of poetic inspiration and the mantric art were developed and elaborated to a degree for which we know no parallel.’ Hamish Henderson believed that Jeannie Robertson was evidence that that tradition continued. Interestingly, Jeannie spoke about her ballad knowledge in the same way we often think of the learning of the Druids – through word of mouth. My Ballads? I learned them from my mother. I never learned them through books – some had been on paper – they were never learned off a paper. That’s certain. But they went from mouth to mouth in their day – the old songs – as my mother said to me. I said to her one day, ‘how did you come to learn your songs?’ ‘Well lassie,’ she says ‘I learned my songs the same way,’ she says ‘as you’re learning them’ she says ‘from me’. I learned them off my mother. The ballads… I’m singing a story when I sing a ballad – and most of them is really history. When I’m singing the song, tae tell ye the God’s truth, I picture it – just as it wis really happening. This quotation is so rich in wisdom! Jeannie Robertson perfectly describes the attributes of the Carrying Stream (and the lineage of the motherline is also interesting in this context). In her description of her process, she shows how the tradition is essentially a generous one. It has to be, or it would not survive. Thus, the songs are passed on through the generations… the river flows on. She also reveals how these songs exist for her in a sort of eternal present, with history and myth intermingling. For those of us with more than a passing interest in the story of the Goddess Cerridwen, we know how easily the eternal present works in the mouths of the Bards. Cerridwen’s story is as fresh now as it was centuries ago because it has been passed on through poetry and song. We can relate to the emotions and the events in Her story just as readily as our ancestors would have done. Hamish Henderson believed that the folk song tradition was a democratic one. Anyone can sing a song and share it with others. No one has ownership of it or takes precedence over another in this process. And, like a stream or a fast-flowing river, the song will pick up many flavours and characteristics of the places and people that it passes through. Nothing is intransigent. Everything can change and flow forward with the movement of the water. This is one reason why the folk collectors in the British Isles often found many different versions of one song. Words were changed and altered to suit different locations but, most often, the real meaning of the song remained. In other instances, new verses would be added to a song. People were not afraid to create something new from an older tradition. In our Cerridwen tradition, we practice something very similar. Our own Cerridwen song, which was first brought into being by Priestess Zindra Andersson at a Dark Moon Ritual, is added to each year – each Spiral of initiated Priest-esses compose a new verse, and so the Carrying Stream of Cerridwen’s inspiration flows on. Mother of the Darkness Mother of the Darkness, Hear our song, Mother of the Darkness, Hear our song. Take us to your cauldron, hold us when we die within. Show us what we need to see, Heal our wounds and set us free. From the darkness we find voice, Help us to accept our choice. From the cauldron we’re reborn, Hear our truth we are transformed. Bless us as we sing to you, shine your light and guide us through. Transformation makes us new, We found our light in you. Mother of the Darkness, Hear our song, Mother of the Darkness, Hear our song. Last month, we held our Avalon Cauldron Gathering in the Assembly Rooms in Glastonbury. [Cerridwen Song Brew and altar. Image Credit: Elan] During our Cerridwen Song Wheel workshop, nine Cerridwen Song Priestesses represented the aspects of the Song Wheel. These Priestesses took on the mantle of Cerridwen’s birds and the magic which was brought through that day was potent. The workshop was the culmination of a year and day (so far!) exploring Cerridwen’s Song Wheel and the part which song and music plays in our understanding of the nature of Cerridwen. She is the Goddess of the Bards and, as the different aspects of the Wheel came through, so too, did the singing of Nature’s Bards – the birds. As each of the nine took their place on the wheel – Robin, Blackbird, Hawk, Wren, Kingfisher, Nightingale, Raven, Heron and Owl – an interesting thing happened. The birds did not always stay in one place. They were quite ‘flighty’, which is perhaps understandable given their nature as creatures of air. Most significantly, another bird – the Lark – often attempted to join the nine. The Lark did this subtly, in slips of my tongue when discussing Cerridwen’s song birds. She would slip in unnoticed as I typed up notes and I would have to correct myself later. I was in no doubt that the nine birds of the Song Wheel were the right ones – I had followed signs, visions and my intuition in this process. But I also pay attention to seemingly innocent mistakes – who was this bird who seemed intent on gatecrashing Cerridwen’s ceilidh? I almost felt a little sorry for the Lark. After all, this bird is a beloved subject in numerous folk songs in Britain and Ireland. For example, ‘The Lark in the Morning’ beautifully describes the habit of the Lark who will sing at the break of day: The lark in the morning she arises from her nest And she ascends all in the air with the dew upon her breast, And with the pretty ploughboy she’ll whistle and she’ll sing, And at night she’ll return to her own nest again. Lark by Dae Jeung Kim Pixabay Larks will sing high up in the air, with their chirrups starting just after they lift off from the ground. Their sustained and complicated songs mesmerise potential mates and strengthen existing bonds between pairs. While reading Andrew Millham’s Singing Like Larks: A Celebration of Birds and Folk Songs, I chanced upon a piece of information which perhaps explains the circling of the Lark around Cerridwen’s Song Wheel: The song of the lark mimics and incorporates songs from other birds… which is no different from folk music. Traditional songs are constantly evolving, merging with each other, and one song can diverge into two entirely different entities, or three, or four! An individual will, perhaps without even thinking, alter a song in melody, rhythm and lyrics to satisfy their own personal artistry. The lark certainly does this too. The rather mischievous appearance of the Lark in the already formed Song Wheel of Cerridwen was perfectly understandable given this fact (and it was further confirmation to me that this intuitive Wheel has a basis in the natural world and holds within it an innate knowledge of the native wildlife of Her landscape). The Lark was simply mimicking the Song Wheel birds as she always does! And, by extension, I realised that the Lark is also a beautiful symbol of the Carrying Stream; like the metaphorical river of folk song, she picks songs up from others, tries them out for size, and changes them accordingly. Like Cerridwen’s rivers of inspiration, which flow through our inner and outer landscapes, we need to move with the currents, change and adapt, so that inspiration (be that in the form of song, poetry or other creative endeavours) remains fresh. Cerridwen is the Goddess of Inspiration and She is also the Goddess of Transformation. The songs of our ancestors – the ‘folk’ in folk songs – are our legacy. They belong to us. They belong to everyone. Like the Goddess who inspired their conception, they are living entities in their own right, which deserve to be honoured and respected. The greatest honour we can give a song is to sing it out into the world and pass it on to new generations. Blessed Be Elan, Priestess of Cerridwen West Lothian, Scotland Instagram: @elan_and_the_hare Elan is a scholar, writer and editor in the field of Celtic Studies. She has a PhD in Gaelic poetry and teaches university classes in Celtic culture and literature.](https://cerridwen.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Priestess-Elan.jpg)

Instagram: @elan_and_the_hare

Elan is a scholar, writer and editor in the field of Celtic Studies. She has a PhD in Gaelic poetry and teaches university classes in Celtic culture and literature.