Songs of Belonging: The Wild Mystery of Singing Ourselves Home

Music and magic, exquisitely woven together, are an irresistible and powerful combination. Priestess Elan shares how song has carried her on her journey with Cerridwen and transformed into a wonderful new offering as part of the Priestess of Cerridwen training.

It is almost a year since I began this column in our newsletter; the season of Earth heralds a full cycle of newsletters before we return into the arms of the Initiatrix to begin again. I began this column as ‘Ethnographic Escapades of a Priestess’ and the idea had been, back in October 2022, to spend a year looking at the folk customs and folk music of the British Isles, exploring the seasons through the lens of our folk traditions and, most significantly, to connect them to Cerridwen and my journey along the path of being Her Priestess.

Of course, in true Cerridwen fashion, I found my newsletter columns being consistently transformed. It should not really be surprising to me at this point – Cerridwen very often has other ideas for all of us, and, as long as we follow the breadcrumbs She leaves for us, we find ourselves in infinitely more interesting places and we are all the richer for it. This newsletter column has slowly transformed through Cerridwen’s guidance.

As I find myself in the season of Earth, with my feet planted firmly on the ground, I see that the roots which have grown from this newsletter and which have been feeding and nurturing me through Her dark soil have been connected to my continued work with Cerridwen’s Song Wheel. The songs of wren and hare, of faerie queens and earthly mothers’ lullabies, which I have researched over the last year, have all found their place in Cerridwen’s Roundhouse of Song.

I have come to realise that the folk songs of Wales, England, Scotland, and Ireland, which I hold so dear to my heart, have Cerridwen’s mark of inspiration upon them. These songs are magical and they still exist in our culture because they remain relevant. But furthermore, so many of them contain traces of the Goddess of Inspiration and Her messages; they are spellsongs hidden in plain sight. I now realise that this has been the true reason for this journey around the year with my newsletter column. I had to understand this in my bones (and not just on an intellectual level) if I am to carry the work of the Song Wheel forward into a new year.

I thought, in writing this column, that I was searching for songs and folklore, but now I understand it was actually the songs that were looking for me. These songs, and the songs that will come through from our own Cerridwen Kin in the future, have found the place deep within me which is still open to the old ways – the place within me which is alive with the energy of song magick. Once this had been activated, I do not believe that there was any going back. Songs will never appear the same again – Cerridwen speaks through even the most outwardly simple of songs and, interestingly, it is often the connection between the song and the land, which has had the strongest effect on me. I wonder why that is? For example, why would a Scottish or Irish song that speaks of land and belonging connect me so firmly to Cerridwen? I think the answer lies within. When we call in our Goddess of Inspiration, She is within us as well as in the land that surrounds us. Every tree and plant, every rock and hill, takes on new meaning when the Awen flows through us.

In this year of searching for song and folklore, I have realised that, as long as I have Her by my side, no matter where I plant my feet, there She will be, and our voices meet and merge with our ancestors and those who will come after us. For me, the song has been the key which has unlocked the door into other worlds within the physical landscape.

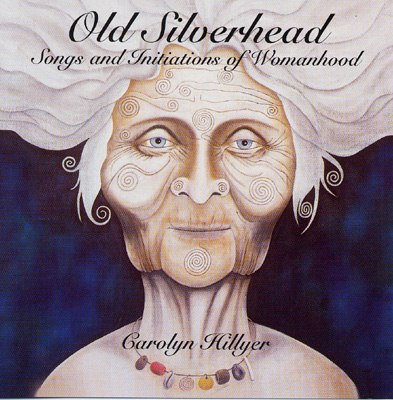

This summer, I was on holiday in Devon and, by luck or synchronicity, I finally managed to see Carolyn Hillyer and Nigel Shaw perform their beautiful music. I have been a fan of Carolyn Hillyer’s music since the mid 1990s when, as a teenager, I picked up a cassette tape of Old Silverhead in a shop in Glastonbury.

(Image Credit: Carolyn Hillyer. For music and art by Carolyn hillyer, visit Seventh Wave Music, Dartmoor – Nigel Shaw & Carolyn Hillyer)

Her music has grown with me; I constantly find new layers to her songs but, when I hear her songs of womanhood on that first album I bought – songs such as ‘In my Mother’s Country’ – I am taken back to the inner landscape where I discovered the Goddess for the first time. It was an awakening and Caroyn Hillyer will always be an important part of my Goddess and song lineage even though we are not related and have never met! I had always yearned to hear her in concert but, in the past, I would find myself missing her concerts by a day here or there when I was down in the southwest. This time, the stars aligned, and I was able to attend a lunchtime concert in Chagford, on Dartmoor. Nothing prepared me for the emotion I felt as the concert began. I am not ashamed to admit that I spent the whole concert with tears running down my cheeks. When I took time afterwards to think on the reason for these tears, it dawned on me that it was the perfect connection between song and land, which had moved me so deeply. To hear Carolyn’s songs of Dartmoor, accompanied by Nigel’s flutes made from Dartmoor wood, while sitting within the land of Dartmoor obviously proved to be a heady brew and my emotions bubbled up and spilled over!

One song left a lasting impression on me – ‘Wounds of Winter’. It is written in Carolyn’s version of proto-Celtic and is an honouring of the ancestral spirits of both the north-west mountains and the south-west moors of the British Isles. The translation reads:

To the highlands from the valleys

We go on paths trodden by deer

This is our secret home

It is all that we have known

These mountains

Where our mothers still stand.

This amber and copper

Honour our mothers’ land

This whetstone and grinding rock

Honour our mothers’ land

This warm vessel of honey

Honours our mothers’ land

On the wild and free mountains

Where our mothers still stand.

These blessings of summer

Honour our mothers’ land

This bellowing stags

Honours our mothers’ land

These wounds of winter

Honour our mothers’ land

On the wild and free mountains

Where our mothers still stand.

I know that it is the ancient language of this song, which speaks to me on a very deep level. Like an archaeologist, we can go down into the earth, layer upon layer, and find evidence of ourselves (and our songs) thousands of years ago. The mother tongue and the lands we call home are inextricably linked, and while we may not speak or even know this ancient language in a conscious way anymore, hearing a song like ‘Wounds of Winter’ awakens us to who we still are, at the root of everything. Perhaps song will always take us into that state more easily than any other method. Carolyn sings the refrain, ‘truth moves in our bones’ at the end of this song, highlighting the Mystery; these folksongs will always move in our bones, but it is up to us to open ourselves to the truth of this.

It is also worth stating that song magick is, and should always be, democratic in its outlook – songs and the sense of belonging which they often instil in us, is something which should be available to all who wish to honour these songs, regardless of the land that they call home. Some of the most poignant and heartfelt songs to land have been composed by those who were not born on that land but it does not diminish their love and connection to it – we are all citizens of the earth. A good example of this in the Celtic tradition is the song attributed to Deirdre of the Sorrows, who fled from King Conchobar of Ireland with her lover Naoise and his brothers, to Argyll in Scotland.

(Image Credit: Aileen MacNicol)

The oldest song in Scotland is believed to be Deirdre’s haunting farewell to her adopted land, before she returned to Ireland (and ultimately, to her death). Even in the translation from the original Gaelic, which can be found in the Glenmasan manuscript, the importance of placenames and specific landmarks is palpable.

My love to thee, yonder land in the east,

and sad it is for me to leave the sides of thy bays and harbours,

and of thy smooth-flowered, lovely meadows,

and of thy green-sided delightful knolls.

And little did we need to do so.

A land dear (to me) is you land in the east,

Alba with (its) wonders,

I would not have come hither out of it

Were I not coming with Naisi.

Dear are Dun-fidhga and Dun-finn;

Dear is the Dun above them;

Dear is Inis Draigen, also;

And dear is Dun Suibhne.

Caill Cuan!

To which Ainnle used to resort, alas!

Short I deemed the time

With Naisi on the coast of Alba.

Glen Laidh!

I used to sleep under a lovely rock;

Fish and venison and fat of badger;

That was my food in Glen Laidh.

Glen Masain!

Tall its sorrel, white its tufts;

We used to have unsteady sleep

Above the shaggy Inver of Masain

Glen Etive!

There I built my first house:

Lovely its woods after rising

(A cattlefold of the sun is Glen Etive).

Glen Urchain! (Glenorchy)

It was the straight, fair-ridged glen:

Not more gallant was a man of his age

Than Naisi in Glen Urchain!

Glen Daruadh (Glendaruel)

Dear to me each of its native men;

Sweet the cuckoo’s note on bending bough,

On the peak above Glen Daruadh.

Dear (to me) is Draigen with its great beach ;

Dear its water in pure sand :

I would not have come out of it from the east,

Were I not coming with my beloved.

(Image Credit: Aileen MacNicol)

Deirdre expertly conjures that innate sense of cianalas (the Gaelic word for longing, which specifically relates to the land – ‘homesickness’ in English is not really an adequate translation for the meaning of this Gaelic word). Hiraeth – a Welsh word that has no direct English translation – is also a word I would equate with this type of song. The University of Wales likens it to a homesickness tinged with grief and sadness over the lost or departed.

A year on from my initiation as a Priestess of Cerridwen, I have felt that cianalas and hiraeth in another sense; so many of us are longing for Avalon and Bala because we have put down our spiritual roots in these places. While we always have Cerridwen with us, our spiritual homes will always exert an influence upon us – the land is not just a backdrop but is a part of our Priestess-selves and our relationship with Goddess. We yearn for it just as we yearn for a time in the past when our sisterhood was intact – a time before the fall of the temples and the subsequent need for remembering. Carolyn Hillyer’s proto-Celtic song of ancestral land and Deirdre’s Gaelic song to her adopted land both tap into this love and connection. In this season of Earth, may we find our own connection to the lands of our hearts and sing that connection alive once more.

Blessed Be

The Cerridwen Song Wheel online module will begin in November 2023 in the Temple College of Avalon and is open to those on the Second Spiral of their Priest-ess of Cerridwen training. The module can also be taken by those not currently on the Priest-ess training. Those who complete the full module will become the first Songbirds of Cerridwen. For enquiries, please contact Elan at emdym@hotmail.com

Elan, Priestess of Cerridwen

West Lothian, Scotland

![In this season of Water on Cerridwen’s Wheel of the Year, we have reached the point when summer is properly upon us; many people are turning to the thought of holidays and others are gearing up for music festivals across the country. This is the time when ‘going with the flow’ seems like a good plan! Hard work can wait for a while – perhaps ‘messing about on boats’ on the river as the Water Rat said to the Mole really is the answer. As I explore the folk song tradition through the lens of Cerridwen of Water, I am thinking of a concept, which has its source in the symbolism of water and which never fails to inspire and move me – that of the Carrying Stream. The Carrying Stream comes from a poem, composed by the Scottish folk collector, ethnologist and poet, Hamish Henderson. Should there be a name and credit here? These are words from an elegy, which he wrote for himself: Change elegy into hymn, remake it – Don’t fail again. Like the potent Sap in these branches, once bare, and now brimming With routh of green leavery, Remake it, and renew. Maker, ye maun sing them … Tomorrow, songs Will flow free again, and new voices Be borne on the carrying stream. This Carrying Stream has come to mean being part of the passing on of a tradition, mainly through music and culture. Henderson, who was one of the first folk collectors in the School of Scottish Studies in Edinburgh (a treasure house of tradition and the ‘voice of the people’ established in 1952 in George Square, at the University of Edinburgh). He knew the value of song and tradition and he travelled all over Scotland, collecting songs and stories from the people he met. He is well-known for the relationships he formed with the Traveller communities – those who were ‘Summer Walkers’ and the berry pickers of Blairgowrie. It is significant that it was often the Travelling community who were the best source of knowledge for the ‘old songs’. These people were often shunned and derided and yet it was their characteristic movement across the land (the reason for many peoples’ distrust of them) that enabled them to pick up songs from many places and carry them forward. Henderson’s ‘discovery’ of the ballad singer, Jeannie Robertson was described by Henderson as ‘the most important, single achievement of my life – the thing of which I am most proud.’ Should there me a name and credit here? She was a Traveller with a vast storehouse of traditional knowledge and song. In 1941, in Poetry and Prophecy, the archaeologist N.K. Chadwick had written that ‘among the early Celtic peoples the inculcations of poetic inspiration and the mantric art were developed and elaborated to a degree for which we know no parallel.’ Hamish Henderson believed that Jeannie Robertson was evidence that that tradition continued. Interestingly, Jeannie spoke about her ballad knowledge in the same way we often think of the learning of the Druids – through word of mouth. My Ballads? I learned them from my mother. I never learned them through books – some had been on paper – they were never learned off a paper. That’s certain. But they went from mouth to mouth in their day – the old songs – as my mother said to me. I said to her one day, ‘how did you come to learn your songs?’ ‘Well lassie,’ she says ‘I learned my songs the same way,’ she says ‘as you’re learning them’ she says ‘from me’. I learned them off my mother. The ballads… I’m singing a story when I sing a ballad – and most of them is really history. When I’m singing the song, tae tell ye the God’s truth, I picture it – just as it wis really happening. This quotation is so rich in wisdom! Jeannie Robertson perfectly describes the attributes of the Carrying Stream (and the lineage of the motherline is also interesting in this context). In her description of her process, she shows how the tradition is essentially a generous one. It has to be, or it would not survive. Thus, the songs are passed on through the generations… the river flows on. She also reveals how these songs exist for her in a sort of eternal present, with history and myth intermingling. For those of us with more than a passing interest in the story of the Goddess Cerridwen, we know how easily the eternal present works in the mouths of the Bards. Cerridwen’s story is as fresh now as it was centuries ago because it has been passed on through poetry and song. We can relate to the emotions and the events in Her story just as readily as our ancestors would have done. Hamish Henderson believed that the folk song tradition was a democratic one. Anyone can sing a song and share it with others. No one has ownership of it or takes precedence over another in this process. And, like a stream or a fast-flowing river, the song will pick up many flavours and characteristics of the places and people that it passes through. Nothing is intransigent. Everything can change and flow forward with the movement of the water. This is one reason why the folk collectors in the British Isles often found many different versions of one song. Words were changed and altered to suit different locations but, most often, the real meaning of the song remained. In other instances, new verses would be added to a song. People were not afraid to create something new from an older tradition. In our Cerridwen tradition, we practice something very similar. Our own Cerridwen song, which was first brought into being by Priestess Zindra Andersson at a Dark Moon Ritual, is added to each year – each Spiral of initiated Priest-esses compose a new verse, and so the Carrying Stream of Cerridwen’s inspiration flows on. Mother of the Darkness Mother of the Darkness, Hear our song, Mother of the Darkness, Hear our song. Take us to your cauldron, hold us when we die within. Show us what we need to see, Heal our wounds and set us free. From the darkness we find voice, Help us to accept our choice. From the cauldron we’re reborn, Hear our truth we are transformed. Bless us as we sing to you, shine your light and guide us through. Transformation makes us new, We found our light in you. Mother of the Darkness, Hear our song, Mother of the Darkness, Hear our song. Last month, we held our Avalon Cauldron Gathering in the Assembly Rooms in Glastonbury. [Cerridwen Song Brew and altar. Image Credit: Elan] During our Cerridwen Song Wheel workshop, nine Cerridwen Song Priestesses represented the aspects of the Song Wheel. These Priestesses took on the mantle of Cerridwen’s birds and the magic which was brought through that day was potent. The workshop was the culmination of a year and day (so far!) exploring Cerridwen’s Song Wheel and the part which song and music plays in our understanding of the nature of Cerridwen. She is the Goddess of the Bards and, as the different aspects of the Wheel came through, so too, did the singing of Nature’s Bards – the birds. As each of the nine took their place on the wheel – Robin, Blackbird, Hawk, Wren, Kingfisher, Nightingale, Raven, Heron and Owl – an interesting thing happened. The birds did not always stay in one place. They were quite ‘flighty’, which is perhaps understandable given their nature as creatures of air. Most significantly, another bird – the Lark – often attempted to join the nine. The Lark did this subtly, in slips of my tongue when discussing Cerridwen’s song birds. She would slip in unnoticed as I typed up notes and I would have to correct myself later. I was in no doubt that the nine birds of the Song Wheel were the right ones – I had followed signs, visions and my intuition in this process. But I also pay attention to seemingly innocent mistakes – who was this bird who seemed intent on gatecrashing Cerridwen’s ceilidh? I almost felt a little sorry for the Lark. After all, this bird is a beloved subject in numerous folk songs in Britain and Ireland. For example, ‘The Lark in the Morning’ beautifully describes the habit of the Lark who will sing at the break of day: The lark in the morning she arises from her nest And she ascends all in the air with the dew upon her breast, And with the pretty ploughboy she’ll whistle and she’ll sing, And at night she’ll return to her own nest again. Lark by Dae Jeung Kim Pixabay Larks will sing high up in the air, with their chirrups starting just after they lift off from the ground. Their sustained and complicated songs mesmerise potential mates and strengthen existing bonds between pairs. While reading Andrew Millham’s Singing Like Larks: A Celebration of Birds and Folk Songs, I chanced upon a piece of information which perhaps explains the circling of the Lark around Cerridwen’s Song Wheel: The song of the lark mimics and incorporates songs from other birds… which is no different from folk music. Traditional songs are constantly evolving, merging with each other, and one song can diverge into two entirely different entities, or three, or four! An individual will, perhaps without even thinking, alter a song in melody, rhythm and lyrics to satisfy their own personal artistry. The lark certainly does this too. The rather mischievous appearance of the Lark in the already formed Song Wheel of Cerridwen was perfectly understandable given this fact (and it was further confirmation to me that this intuitive Wheel has a basis in the natural world and holds within it an innate knowledge of the native wildlife of Her landscape). The Lark was simply mimicking the Song Wheel birds as she always does! And, by extension, I realised that the Lark is also a beautiful symbol of the Carrying Stream; like the metaphorical river of folk song, she picks songs up from others, tries them out for size, and changes them accordingly. Like Cerridwen’s rivers of inspiration, which flow through our inner and outer landscapes, we need to move with the currents, change and adapt, so that inspiration (be that in the form of song, poetry or other creative endeavours) remains fresh. Cerridwen is the Goddess of Inspiration and She is also the Goddess of Transformation. The songs of our ancestors – the ‘folk’ in folk songs – are our legacy. They belong to us. They belong to everyone. Like the Goddess who inspired their conception, they are living entities in their own right, which deserve to be honoured and respected. The greatest honour we can give a song is to sing it out into the world and pass it on to new generations. Blessed Be Elan, Priestess of Cerridwen West Lothian, Scotland Instagram: @elan_and_the_hare Elan is a scholar, writer and editor in the field of Celtic Studies. She has a PhD in Gaelic poetry and teaches university classes in Celtic culture and literature.](https://cerridwen.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Priestess-Elan.jpg)

Instagram: @elan_and_the_hare

Elan is a scholar, writer and editor in the field of Celtic Studies. She has a PhD in Gaelic poetry and teaches university classes in Celtic culture and literature.

This is such a delight to read, and for those of us that lack the talent of singing (speaking for myself), I absolutely love listening to all the sisters that have been inspired to sing with the guidance of Cerridwen. Elan, you are a gift to our Cerridwen Kin and you are adored. I enjoy listening and humming or singing in my own space. Thank you for your musical talent.